Nouvelle Chronique de Jazz Journal June 2017 by Micheal Tucker Merci beaucoup, thank you !

http://www.jazzjournal.co.uk/jazz-latest-news/1222/

Concerts avec Pier Paolo Pozzi, Gilles Naturel, Blaise Chevallier, Olivier Cahours, François Fuchs et moi-même

Paris: art by day, jazz by nightMichael Tucker visits an exhibition devoted to artist Karel Appel and spends three nights in the company of the immensely literate pianist Christian Brenner

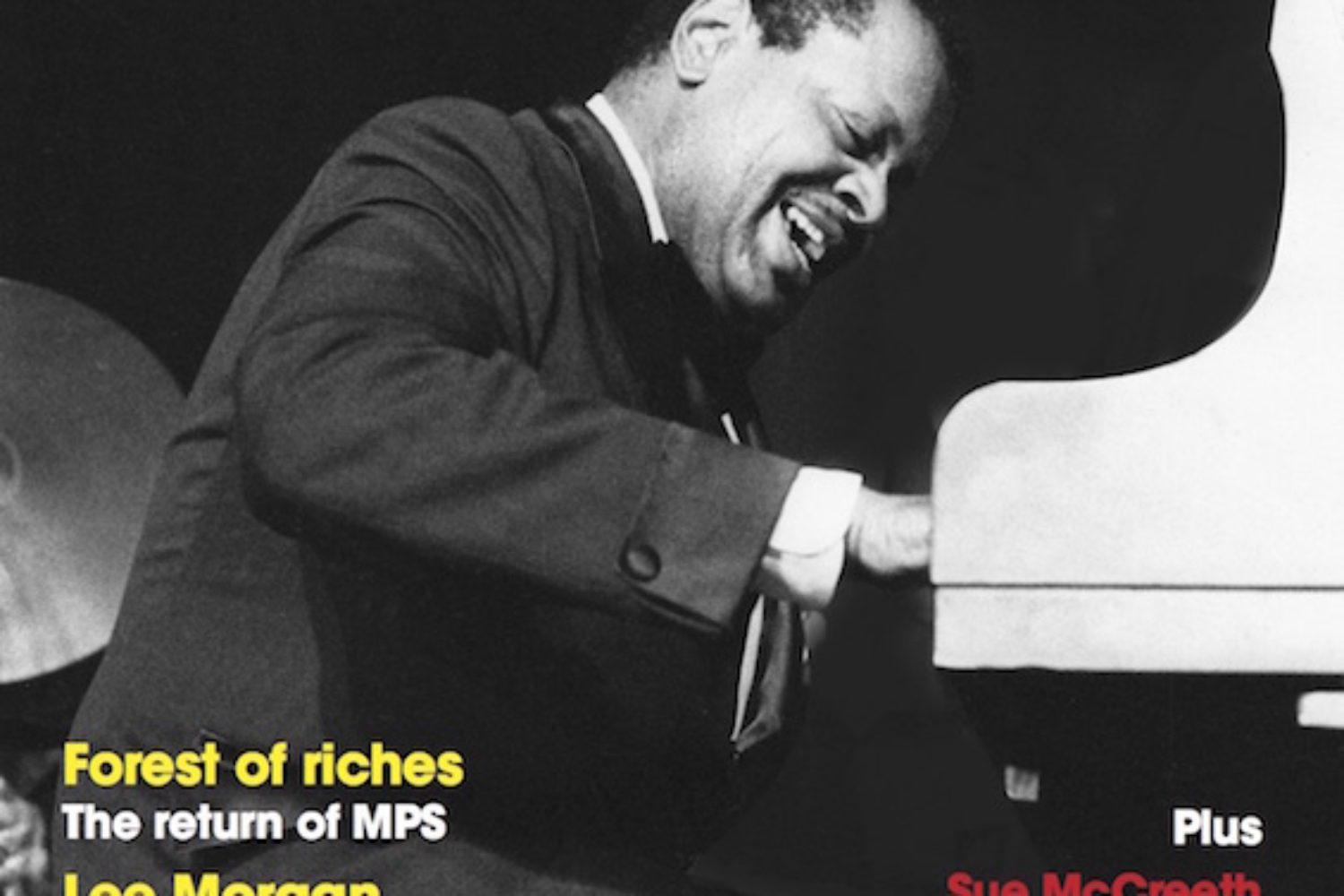

Born in Amsterdam, Appel lived in Paris from 1950 to 1977, when he produced some of his most arresting works. Many of these were strongly influenced by what – following various visits to New York – Appel saw as the overall import of jazz: namely, its fundamental life-affirming vitality. He made some striking portraits of musicians, including Count Basie (pictured right), but the essence of the influence of jazz on Appel is to be found in the overall spontaneity of his working methods, the freely improvised mix of exuberant swathes of high-keyed colour and vigorously worked line. I say exuberant, but there was also a strong sense of the absurd, the grotesque and the tragic in Appel. He said once, “I paint like a barbarian, in a time which is barbaric”. Like many painters of his generation, Appel was strongly marked by the horrors of World War Two and the subsequent tensions of the Cold War. All such characteristics were evident in a terrific exhibition which ran from the late 1940s through to Appel’s last years. It included a good many polychrome sculptures and ceramic pieces besides such archetypal paintings as Shriek In The Grass (1947), Carnaval Tragique (1954) and Archaic Life (1961). A highlight of the show was the opportunity it afforded to view the last-named piece – one of the largest and most powerful of Appel’s paintings, usually on view at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam – in close proximity to a showing of a substantial extract from a key film made about Appel in 1961, The Reality Of Karel Appel. Directed by Jan Vrijman, the film focuses on the making of Archaic Life. We see Appel, not so much painting the canvas as attacking it with both hands, as one thickly laden spatula after another splashes paint into and across the emergent image. In part two of the three-part, largely electronic and richly percussive Barbarous Music LP which Appel released in 1963, the painter can be heard declaiming “I don’t paint, I hit!”. While Vrijman’s excellent film drew upon some of what would become Barbarous Music it also featured memorable, specially commissioned music from Dizzy Gillespie, now up-tempo, staccato and burning, now blues-soaked and musing. Fortunately, some of Gillespie ‘s work featured in the extract of the film which was shown on loop in the Appel show. In Spring 2009 I visited Paris to see the large exhibition The Century Of Jazz: Art, Cinema, Music from Picasso to Basquiat at the Musée du Quai Bramly. Astonishingly, Appel did not feature in the show; nor was he (or Vrijman) to be found anywhere in the 450-page catalogue published to accompany this would-be comprehensive affair. The exhibition Art Is A Celebration, A Party! and the accompanying catalogue (which contains many memorable black and white images from Vrijman’s film by photographer Ed van der Elsken) went some considerable way to making up for this unaccountable oversight. It has often been pondered whether the word jazz is best taken as noun or verb. The opportunity the exhibition afforded to experience Appel’s Archaic Life – a key work of the 20th century, deeply influenced by jazz – as both shape-shifting process and completed product was quite exceptional. If this film from 1961 (the year of Coltrane’s legendary Chasin’ The Trane blues from Live At The Village Vanguard) did much to reinforce the long-standing myth that the over-arching image of jazz must be one of a music of improvised vitality, it also helped question any such myth and image. Appel is seen splashing paint on his canvas, like a demented drummer; but he is also seen standing back from his work, contemplating the results of his actions and choosing one rather than another colour for the next assault. Similarly, the range of tone and line exploited by Gillespie in his music for the film gives the lie to any simplistic notion of jazz as pure unmediated expression – the kind of myth that later in the decade would drive some of the wilder and ultimately less productive moments of free jazz.

On this trip I was able to experience heartening confirmation of the long-standing faith of many an enthusiast of the music: namely that, at its best, jazz is able to dissolve the ostensible opposites of past and future, individual and group, structure and improvisation, intellect and emotion into an inspiring, even healing, confluence of affinities, aspiration and achievement. Three nights on the Left Bank spent listening to the very fine French pianist Christian Brenner offered contrasting yet complementary counterpoint to Appel’s take on jazz, as this immensely literate musician led three diverse yet equally invigorating and enriching groups at the Café Laurent. The first night featured Brenner (born 1958) with his compatriot, acoustic bassist Gilles Naturel (born 1960) and Italian drummer Pier Paolo Pozzi (born 1964) (pictured above left). As Brenner remarked in his programme notes, the music sought to explore and refresh relations between classic, modern and contemporary jazz, drawing upon Brenner’s own finely crafted, often Latin-inflected compositions as well as e.g., Ellington, Monk and Gershwin, Kern, Rodgers and Porter, Arthur Schwartz, Victor Young and Henry Mancini, Charlie Parker and Wayne Shorter, Kenny Barron, Carlos Jobim and others. One of those others was Miles Davis: I entered the intimate and welcoming space that is Café Laurent to the classic strains of All Blues, which generated a typically energising solo from the ever-alert Pozzi, as incisive as it was imaginative. Someday My Prince Will Come and Corcovado were equally delightful, while a very different emotional register distinguished beautifully sustained readings of You Don’t Know What Love Is and When I Fall In Love. Over the many years I’ve had the pleasure of hearing the classically trained Brenner, a consistent feature of his music has been the way his various groups allow the music to breathe. Giles Naturel is often key here. For many years now, Naturel has been first-call choice for Benny Golson whenever he tours Europe, which tells you much about Naturel’s quality. A Paul Chambers and Oscar Pettiford man, Naturel has a lovely warm sound and an enviable ability to let each note come to fully rounded life within the overall drive and bounce of a swinging line. He is also an outstanding arco player, who has spent enjoyable times with Slam Stewart and Major Holley. Whether pizzicato or arco, his playing was right in the pocket, while also slipping organically between dynamically astute, smile-inducing duets with Brenner and Pozzi.

Pozzi – a drummer of both multi-layered power and exquisitely textured dynamic precision, who can play like the wind – was always present. He is able to draw upon considerable experience: he played with Tommy Flanagan in Paris at the end of the 1990s and, a few years later, featured Paolo Fresu on his first recording as leader. Each night Pozzi gelled beautifully with the different bass players Brenner chose. On the second night, Blaise Chevallier – a Scott LaFaro and Eddie Gomez enthusiast – brought more of a cross-phrased edge to the music, perfect for Monk’s Well You Needn’t, a crisply sprung Softly As In A Morning Sunrise and, in conclusion, an extensive and mellow blues. On the final night, Olivier Cahours – a fine, essentially lyrical guitarist who appeared on Brenner’s first release, the 2005 Influences Mineures – and bassist François Fuchs (pictured right) chose to add a small touch of amplification to the proceedings; they shone especially on Blue Monk and There Will Never Be Another You. A most thoughtful, intelligent and sensitive man, blessed with a great touch, Brenner performed one special new composition of piquant lyrical reflection, precipitated by the recent terrorist atrocity in Manchester. Throughout the three nights he mixed diverse harmonic richness and more open voicings, tender lyricism and assertively sprung rhythm, limpid reflection and blues-clipped grooves. Overall, you could say that, while Appel chose to hit, Brenner prefers to caress. He is currently working on two new CDs and in December this year he will travel to Cambodia to lead two groups with, among others, Stéphane Mercier (as) and Damon Brown (t) at a major festival in Phnom Penh. It would be nice to think that, sometime soon, an enterprising promoter in Britain might consider inviting Brenner to cross La Manche and treat us to his special take on many an aspect of what was once so important to Karel Appel: the vitality of jazz. The Karel Appel exhibition in Paris runs until 20 August 2017. Christian Brenner’s latest CD Les Belles Heures was given a five-star review in JJ 1216. Relax with the luxurious print edition of Jazz Journal and enjoy more jazz news, reviews, features and debate. |

As spring turns to summer there are always plenty of good reasons to visit the City of Light. A big draw for me this year was the large exhibition Art Is A Celebration, A Party! at the Musée D’Art Moderne, by the jazz-loving painter and sculptor, poet and printmaker Karel Appel (1921-2006).

As spring turns to summer there are always plenty of good reasons to visit the City of Light. A big draw for me this year was the large exhibition Art Is A Celebration, A Party! at the Musée D’Art Moderne, by the jazz-loving painter and sculptor, poet and printmaker Karel Appel (1921-2006). Over half a century later, at a time when recent tragic events underline how much the issue of barbarism has taken on a newly grotesque and grimly urgent aspect, questions concerning the overall import of jazz are no less relevant or pressing than they were during the early years of Appel’s emergence as a painter of international consequence.

Over half a century later, at a time when recent tragic events underline how much the issue of barbarism has taken on a newly grotesque and grimly urgent aspect, questions concerning the overall import of jazz are no less relevant or pressing than they were during the early years of Appel’s emergence as a painter of international consequence. Oscar Peterson used to talk about the “three-in-one” interaction he sought in his various trios. There was plenty of such interaction on these Paris nights, the first two delivered (as is usual at Café Laurent) with no amplification.

Oscar Peterson used to talk about the “three-in-one” interaction he sought in his various trios. There was plenty of such interaction on these Paris nights, the first two delivered (as is usual at Café Laurent) with no amplification.